Acclaimed memoirist, writing tutor and author of five books Cathy Rentzenbrink joins us for an honest, frank and occasionally strongly worded conversation. We explore how the ‘rules’ we come to believe about our writing become myths that aren’t necessarily true. And why we shouldn’t always believe what other writers tell us about their writing process. Read the full transcript below or watch the video on YouTube.

Welcome Cathy Rentzenbrink

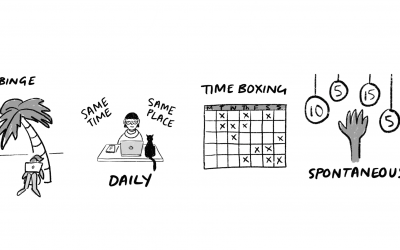

Bec Evans: Welcome everybody to tonight’s Written Conversations. It’s a series of online chats with writers and about writing. I’m Bec, I’m the co-author of Written: How to Keep Writing and Build a Habit That Lasts. And tonight we are exploring some of the themes that come up in chapter one of the book, which is called Break the Rules.

I am joined by Cathy Rentzenbrink and I’m going to give her a full introduction in a second. But first, how it’s going to work this evening. This event is live, so please do add comments to the chat. If you’ve got questions, we’re going to hopefully get to them at the end of the session. And if you are watching this on catch up, do like follow, comment, you know the drill.

So let’s get started. I’m here with Cathy Rentzenbrink the author of five books. Her first was a memoir, The Last Act of Love, then Dear Reader on the comfort and joy of books, Write It All Down: A Guide to Putting Your Life on the Page. There’s the wonderful new edition of How to Feel Better, which I thoroughly recommend everyone grabs a copy of, hot off the press. And her novel, Everyone is Still Alive.

Cathy is one of the hardest working people in writing and literary circles. Chairing events, interviewing authors, podcasting. She describes herself as a writer who likes to encourage, and she does that in spades. She supports writers in prison, those learning to read and write. She runs her own Sunday sessions, which are absolutely brilliant, as well as teaching courses for Arvon, Mslexia and Curtis Brown amongst others. And personally I would say she’s one of the wisest, kindest, most generous and also most curious people I have ever met. So welcome, Cathy.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: Thank you. It’s extremely good to be here.

A peek inside Cathy’s writing room 02:12

Bec Evans: So how are you today? I think you are in your writing room, aren’t you?

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I am, yeah. This is my book that’s on the wall behind me at the moment. Actually, I’m pretty good today because I’ve been a little bit ill, but today I’ve got that wonderful feeling of not being ill. And I’ve been writing and that’s been going well and I feel calmer than I sometimes do. So yeah, I’m feeling pretty good and I was looking forward to this. I like you, Bec. I like talking about writing. I felt excited about doing it with people, so I feel good.

Bec Evans: And you have literally got your book on the wall all around you, haven’t you, on post-it notes? So we’ve got a real sneak peek into your process.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: Shall I show you the wall? Look, so it’s going out to the side and it’s going all the way along there. And actually, opposite me, there’s more of it. The bits that were over there started as I’m typing them I’m putting them somewhere else. So I’m really going for it and I’ve just looked over there. So I’ve got another book on that wall and I’ve got another book on that wall.

For ages, I’ve been saying things like, “Oh, what I really want is just a big white wall.” And then I thought, “Well, should I just give that to myself, given that I can now?” I have all these instincts and urges and then I don’t act on them. I just keep trying to joylessly tap it out on a computer because that will save time in the long run, which I don’t actually think is even true.

So yeah, I’m going for it. I could show you the table, trying to remember what’s on it. I mean, I’d just show you how messy it is. It’s just mess, mess, mess. But again, I’m allowing that because that seems to be what I need at the moment at this point in process. So I’ve got piles of paper and peculiar drawings. And look, this is the first bit of manuscript of the book, but I’ve now typed it out and I’ve gone through it and I’m cutting it up and sticking bits of it on the wall, putting it together like that. So it’s a new way of constructing, which I think is working.

Careful or you’ll end up in my next novel 04:38

Bec Evans: I absolutely love it. I am obsessed with writer’s spaces as much as I am with their habits and routines – and I’m sure we’re going to get to those later. So thank you for sharing those. I am going to ask if you can show people your t-shirt because it is one of my absolute favourites. I’ve seen this on Instagram before.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: So there we go, it says, “Careful or you’ll end up in my next novel.”

Bec Evans: So warning what questions get asked [laughs].

Cathy Rentzenbrink: That’s the thing. My friend Lizzie gave me this t-shirt because she is in my novel, or specifically her kitchen is in my novel and her dishwasher is in my novel, with her permission. Got a lot of stuff about her children, carefully done and anonymized, is in my novel and quite a lot of stuff about her husband is in my novel, again with their permission. So it amuses me and I think it’s interesting.

Back to Cathy’s pre-writing days 05:34

Bec Evans: Thank you so much. We can see you in your writing room with everything around you to support you now. I want to take you back to your early or pre-writing days actually. I’m really interested in the beliefs and myths that we take on as writers. In chapter one of Written, Chris and I opened the book with a story about Cheryl Strayed, who is a memoirist, who wrote Wild which went on to be made into an Oscar nominated movie. She’s a bestselling, very successful author.

But before she did that, she judged herself believing that she wasn’t a writer and that she was a working class woman working as a waitress. And she was taking on board pieces of advice such as, “If you don’t write daily, you’re not a proper writer.” And it struck me when I was going through your books that you tell a very similar story, and I’m going to quote this back at you, which can be slightly mortifying, so bear with me. But it’s the idea within it that we can explore. So you wrote:

“I grew up wanting to write but was never encouraged. As I got older, I lost my childhood enthusiasm and more and more I allowed myself to be told that people like me couldn’t be a writer, that it was too hard, too difficult to get published, too impossibly out of reach. So although I’d try, I would give up because when the going got tough, I would brood on this negative belief.”

Cathy Rentzenbrink: It just makes me feel really sad. Not for myself actually, just for the fact that other people get told that. I mean it’s just such a dreadful thing, isn’t it? People are being told that right this second, maybe not this second because they’re not currently in school. But people are told that. And I do find it really sad.

The encouragement of parents 07:39

Cathy Rentzenbrink: That did happen to me and I was very lucky because I had encouraging parents. And I always find this really interesting cause my dad who, I mean he couldn’t read and write until he was an adult, still isn’t good at, still can’t really write very well. But he was always very encouraging of me, I mean much more so I think than my friend’s fathers. So I was very encouraged in the home. But outside of the home, whenever I said something like, “Oh I want to be a writer,” which I did from as soon as I knew what a book was, I wanted to write one.

And I would say it. And I remember saying it because I remember, again, I wanted to be a writer or a detective because I was really into all those Enid Blyton books. So I wanted to either write books or I wanted to be one of the detectives in it. So again, it was that desire. And of course I didn’t know what being a detective would be like. And I’m sure I wouldn’t actually be able, I don’t feel I… I mean, I’ve just got nothing but admiration for people that work in those services that bring them into a lot of conflict with the hard edge of what human beings are capable of. And I actually don’t think that I could do that.

But yeah, I’d say I wanted to be writer or a detective and then people would just say, “Don’t be silly, you can’t do that.”

Then it was always this thing, “If you work very hard, you might be able to become a teacher or get a job in a building society.” Not that there’s anything wrong with either of those things, but that was the only… “If you like writing, work very hard, you might be able to be a teacher.” If you are ambitious, “Work very hard, you might be able to get a job in a building society.”

I did also quite admire the women who worked in the building society in the next village because that was career women for me. And I think these myths, these rules are so written into the culture that they do become a little bit written on the body, and they’re difficult to shunt off. And they’re sort of truth, isn’t it?

People are frightened for you 09:32

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I remember talking about this with Tayari Jones. I interviewed her with her brilliant novel, An American Marriage, and it won the Women’s Prize for Fiction the day after I interviewed her. We talked about this and she said, it’s that people are just frightened for you. They’re just trying to manage your expectations. So it’s not that when kids say they want to be a writer, it’s not that the teacher should necessarily say to them, “That’s an excellent career prospect. That’s going to work out really well financially. It’s a really good idea to do that. You’ll be able to have loads of children and never worry about paying your bills.”

It’s not necessarily that, but it’s just that there’s something that acknowledges a truth isn’t there, that isn’t just like, “You can’t do that because it’s not sensible.” But it’s a wider truth. Like I said, my parents, especially my dad, I mean it’s not that my mom wasn’t encouraging, she was, but my dad’s always been like, “Fuck it, you can do whatever you like.”

Again, he’s almost so uneducated that he almost doesn’t, maybe it’s because he’s Irish, I’ve never been sure of this either. But he doesn’t have that sort of, “We must stay in our place.” vibe about him. He’s much more like, “You want to do it, you just do it.” And he thinks I’m a superhuman because I can read and write and speak the way I do. And I go on the radio. And as he always says, “You sounded very posh on Radio 4.” Which he says in his light Irish accent.

The power of having an encourager 11:03

Cathy Rentzenbrink: So he was always very encouraging, which I’m sure was extremely significant. I think it’s a powerful thing for a woman to have any encourager, but particularly to have a male, to have your dad encouraging you is an astonishing privilege. But equally, I went to university and the first people that ever took it seriously when I said I want to write books, almost the first person I met at university was Sophie, who’s still my best friend. I’m also wearing my lucky writing cardigan, which she gave me for my birthday this year.

But yeah, I said it to her and she was just like, “Yeah.” And then I met her parents and her stepparents and her wider family and they just always treated me like I was going to write books. It was the first time it had ever happened to me that people, that this could be a possible thing. So yeah, quite profound.

How myths come to define us 11:57

Bec Evans: I think it is really profound how these myths, they can come to define us. The beliefs that we have affect our behaviour. So if we are told you’re not a writer and then we start to believe we are not writers, we do stop writing. It happens to so many people very, very early on.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: Well I think so because the other part of the reason why it happens easily is because writing is hard. And all my teaching comes from the place of, yeah, I’m not going to lie to you, writing is really hard. And actually I’m not going to lie to you that making a living at writing is also really hard. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it. I think you should do it, do it.

The thing is basically every time it’s hard, our brain fills up, our mind fills up, our soul fills up, our heart fills up, our bodies fill up with all this crap we’ve scraped up along the way.

All the stuff that the teacher said or maybe that the less encouraging father said, or that everyone said.

All the stuff we’ve read about on the internet, because there’s like an amazing amount of bollocks talked about writing that’s on the internet. We’ve hoovered it all up and every time it gets a bit difficult, it’s just the easiest thing in the world to think, “This isn’t for me. This isn’t meant to be.”

And the reason why I still think it’s a miracle I’ve finished anything, let alone finished five books. But the reason why I’ve done that is because I’ve just learned to not listen, to not give myself doubt, objective weight and value. Well, I don’t keep going when it gets tough, I usually have some sort of variation on a nervous breakdown and start writing another book.

My books exist because I got stuck on another book 13:43

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I realised the other day most of my books exist because I was stuck writing another book. And then it got to the point where I had to finish that book, and then I went back to the other one. I was writing my novel before I even wrote my first book, but then it was supposed to be my second book. But then I wrote my second book and my third book because I was stuck writing that novel.

Bec Evans: That seems a very good tactic that’s worked incredibly well for you. And you were probably told, “No, you need to finish a book before you start another.”

Cathy Rentzenbrink: Yes, not to write more than one thing at a time. Again, and that’s probably very good advice if you can take that advice. I always say to people, “God, yeah, don’t write more than one book at a time unless that’s the only way you can do it.” It’s the only way I can do it. And I think that’s the other thing about advice, which I always think is really the most important thing that I ever want to say at anything.

The important thing about writing advice 14:36

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I’m glad I’ve thought of it, because if I ever do an event, the event can be so lovely and then I will wake up in the night basically wanting to jump out the window because I forgot to say this thing. I’m glad I said this thing, which is that any kind of writing advice, all any writer can really do is say, “This is what works for me.”

It’s everything that works for me, it’s because of who I am, it’s because of how my brain is wired. It’s because of the experiences I’ve had. It’s because of the encouragement I had and the knocks that I had. It’s really super specific. And the thing is, I know that, so I’m really happy to, I’ll splash that about left, right centre.

But the caveat is, people listening, if it doesn’t work for you, just decide, “Well that’s interesting she does it like that. That’s not my way. Maybe the next time I come to one of Bec’s events, the person will be a bit more like me or it’ll resonate more with me.” But that’s the absolute most important thing that you’re always looking for, how you can make it work for you. And that when someone tells you something that’s just like, “That sounds completely bananas.” It might be because you’re really different for them.

Writers lie about their writing process 15:39

Cathy Rentzenbrink: But equally, I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, writers lie a lot because loads of writers don’t want to admit how half-arsed the process is.

Loads of writers don’t want to admit that the table’s really messy and that the book’s in bits, because they’re just too frightened. And I think that writing gurus of mine, none of whom I know in real life, would be like George Saunders, Hillary Mantel, Ali Smith. And when I listen to them, I think, “Oh, that’s my process.” I’m not comparing myself to them as a practitioner, but the process difference isn’t different.

The difference is they seem to be more reconciled with the fact that that’s how it works. Whereas I keep getting angry with myself that I can’t just churn out a book like a good little accountant with a critical path spreadsheet planner. And that’s what the difference is, that again I’m still stuck in this thing of if I was better, that one day I’ll be able to do this better. And at that point, everything won’t look like such a bomb site. And I work with a bomb site.

So that’s the thing, a lot of nonsense is talked about writing. And again, for individual writers, I understand why you do it. I mean I’ve got friends who do it, they self-protect. They say, “Well I had to make something up when they asked, “Where do you get your ideas from?” I couldn’t say, “I don’t fucking know.” So I made up loads of stuff.”

I understand why they do it. But the problem then, everybody in the audience goes off and tries that and then they get disappointed it doesn’t work. And that’s why I was thinking about this, why am I honest about my process? Because I don’t admire my writing particularly. I get why Hillary Mantel, Ali Smith and George Saunders, Max Porter, I get why they can be honest about their process. Because they’re actual geniuses, but I’m not, I’m just a fuck-up who somehow managed to finish five books, a mystery to me.

Then I thought, it’s because, especially if it’s in the service of other people’s writing, it’d be different if I was just on stage talking about a book. But in the service of other people’s writing more than my own fear of my own inadequacy, it’s just this burning need to just tell the truth about what it’s like. And just the horror that I could do to someone else, what anyone has done to me when they say like, “Oh no, you can’t do that. Oh no, well if you can’t make a plan, then you definitely can’t do it.” And, “Well no, if you wanted to write, you’d write like that.” I mean that was about 20 years I basically spent biting my nails and shivering because I could hardly get a word down. All that.

So I just never want to do that to anyone fraudulently. I hope I don’t put people off by telling the truth, but at least if I put people off by telling the truth, I’ve told the truth, haven’t I?

Productivity is personal – figure out what works for you with help from Rapunzel 18:22

Bec Evans: You’ve told the truth! There’s so much in there, Cathy, but I want to pick up on a couple of points. So one thing that we figured out, Chris and I when we were writing the book and working with writers over the past 10, 20 years, is this sense that productivity is personal, that sense that you’ve got to figure out what it is for yourself.

So what did that look like for you? How did you figure out how to write the first book and then it changed when you wrote the second and the third? I mean, how do you keep present with your writing and keep present with your practice?

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I mean, they’re all very good questions. I love talking about the granular detail of it because I think that’s where it’s all at. But again, I just want to caveat it with, it may seem as I explain all this that I always knew what I was doing, but I didn’t.

I tell you what, I thought of this metaphor yesterday. I was talking to a friend, again calming her down because she’s started to panic about various things. Whereas actually she’s very much on the right track. Every time she gets knocked over in the wave of her own despair, she just needs to bring herself back to what she’s trying to do and crack on.

And as I was talking to her, I said, “It’s a bit like in Rapunzel where the prince gets chucked out of the tower and blinded.” I remember I had one of those Ladybird books when I was a girl and I was always struck by this picture of the prince blundering around in the thorns. And I said to her, “It’s just like that. And the only thing I know is that you just have to be like that for a bit. Whereas because you are earlier on in your writing career, every time you feel like that you want to ask for help. It’s not a bad thing to ask for help if someone can help you. But what I’ve learned now is I just have to blunder around in the thorns a bit. And then at some point, don’t know quite why, but it’s something to do with blundering round in the thorns, the fairy godmother will appear and tap my eyes and I will see the answer.”

So that’s the metaphorical thing. Practically, with my first book, I mean, again, I don’t know. It exists, doesn’t it? So I must have done it. But I honestly find difficult.

Cathy’s first book – writing when working and caring for a family 20:30

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I do know how I did it because I was working, I had two jobs, and my son was basically between two and four when I was writing that book, which is really hard work. But what I did was I started trying to write in two shifts a week. And the first time I tried it was on a Saturday night after Matt was in bed and I was just too knackered.

And then I thought… Actually, it wasn’t ‘and then I thought’, I probably cried and got drunk and went to bed and gave up. But then at some point, maybe a couple of weeks later, maybe a couple of months later, I can’t remember, at some point I thought,

“Actually for the book, it needs to be first thing.” But on Saturday night I could do my work emails. I think on Saturday night I could do work, different types of work, the sort of work where I don’t really have to use a brain, just ploughing through my inbox work. I could do that on Saturday night and then I can buy myself, I think I started with three hours.

Ask for advice and learn to reject it 32:41

Bec Evans: And writers change! One thing I really love about your books is you actually ask other people for their advice. And you can be quite horrified by their advice. What did you say in your inspiring addendum in How to Feel Better? You say,

“I find it both comforting and stimulating to map myself against other humans. I like getting tips but I equally enjoy thinking, well, I’d never want to do that.”

It’s that sense of being able to ask for advice and then learn to reject it and trust your senses where that’s not going to work for you.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: The curiosity, which you said about me at the beginning and I really liked that because I do try it all. I think curiosity’s the great antidote to fear and worries about your own inadequacy et cetera. So whenever I can shift into curiosity, and it’s such a good space to be in as well. Because again, it’s something about being curious as well means you’re not judgmental. Which again, that’s not a creative vibe for me.

Basically, being frightened or judgmental just isn’t a good creative setup. So I am very interested in other people, in the granular details of their lives. And I always have been, but even more so at the moment. I love it if someone just tells me what time they eat. Someone told me the other day, “Oh, every time I cook, I make two teas.” So they don’t always cook, but when they do, they always make double portions.

There was just something about that I just thought that’s just really exciting to me somehow. I don’t know why it’s so exciting, but it is. I just like all that granular stuff, I find it very interesting. And again, interesting when I think like, “Oh yeah, I’ll try that.” Or interesting when I equally think, “There’s no way I’m doing that.” But not with any judgement. I think that’s the excitement as well, that we don’t have to be like everyone else. We can be our own selves and they can be their own selves, and that’s the exciting thing for me.

Not that we should all try to somehow morph or dilute into the lowest common denominator of humanity, but that we should just be, “I like doing this. Oh, and you like doing that? Hurrah! Isn’t it nice we both exist?” That kind of thing.

How writers support and encourage other writers 35:10

Bec Evans: You are an encourager of writers. You have worked with so many different people and your Sunday sessions at the moment pulls together a lifetime of thinking about writing and encouraging people to write.

There’s a very famous story, which gets quoted back to you a lot, but I want to talk about it again, which is when Matt Haig talks about in Reasons to Stay Alive how he lacked the confidence to write that book. You were the person who told him to do it. And of course, it has gone on to sell millions. I mean, it’s just a hugely, hugely successful book. He called you one of the most dynamic and frankly brilliant advocates of books, championing their cause and in his case causing them to exist. And of course that happened over wasabi flavoured popcorn.

And it’s a great story but what I found really interesting is that his book came out in 2015, and your first book came out in 2016. So you were in the world of writing, but you weren’t a published writer. You have been encouraging people to write for such a long time. I love that sort of belief. Julia Cameron calls it a believing mirror. You need people to champion you, to give you permission to do something. We often think as writers and we need lots of writers around us, but actually just having someone, as you said, it can be your dad saying you can do this, makes such a difference.

Encouraging Matt Haig to write over wasabi flavoured popcorn

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I was a bookseller for 10 years and I always say it’s very generous of Matt that he put that in the acknowledgement and he often talks about it in podcasts and stuff. And of course, because he is now so super famous, I’ll get a little rush of communications. All friends of mine will say, “I didn’t know you were behind Matt Haig’s book.” Again, just to be clear, I wouldn’t ever myself bring it up. If we’d had that conversation and he didn’t ever tell anyone about it. I wouldn’t go on about it. I wouldn’t think it was my business because again, the creative process is very delicate and fragile.

We had a conversation that was useful to him, but he was then the person that did the stuff that needed to be done. So I don’t have a sense of ownership or anything. I just think it’s really lovely.

What is interesting about it for me is thinking, “Yeah, why was I so confident?” But I’d been a bookseller for 10 years and at the time I was running a literacy charity and what I felt really needed to happen. Matt had written a couple of blogs for Book Trust about mental health.

And again, this is my deep knowledge of my dad as a non-reader. It’s a great gift, I think to me, to have had my dad who couldn’t read and write until he was an adult, still not confident. What I really felt needed to exist about depression, and it’s difficult to remember now, this is a few years ago. There’s loads of awareness now and loads of chat and lots of people talking about it. It was almost like literally nothing, hardly anything.

What I felt needed to exist was a book and I remember saying this – this is going to make me cry – I felt we needed a book so that would work for the 19-year-old boy who can’t get out of bed and doesn’t understand why. And for his father who’s never read a book in his life and doesn’t understand why. So something really simple, bullet points, lists, actively not a literary book made for people who would read, actively something useful but just set out really simply and clearly to slightly explain a little bit about what’s going on. And offer some hope, not in a fraudulent way, but it can happen and it can be all right in the future-ish.

And that’s what I thought was necessary. And lots of people didn’t agree with me. I said to a friend of mine in publishing like, “Oh, I think there should be this book.” This is a very important brilliant person. She just said like, “Ugh, no one will want to buy that.”

Encouragement matters 39:22

Bec Evans: We can’t underestimate how much that encouragement matters. Someone’s put in the chat that you had praised a sentence that they’d written about five years ago, and that gave them the encouragement to keep writing and they’re two thirds of the way through their memoir. Thank you Cheryl for sharing that.

Because it does make a real difference. And I think what we do, even before we write, if we just encourage other people, it can make a huge difference. Just listening to them, hearing your friends talk about their writing and moan about their writing or tell you their writing dreams and just acknowledging that can make such a difference.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: The other reasons why I think Matt Haig is generous in the way he talks about his process is because he will say, he talked about it as an X Factor on Word documents. It shows how long ago that is as because again, the X Factor was on telly. He would just have four word documents going and keep adding to them and sooner or later one of them would slightly rise up to the top. And that’s how he was doing it.

At the time I was trying to write, but I was very bowed down by the fact that I was probably doing it wrong. And I tell you the other thing he did for me was because I was trying to write my book and I again was just stuck and didn’t think I could do it. I didn’t really tell people I was doing it, but for some reason I had confided in him and he said, “How’s it going?”

I said, “It’s just awful. I don’t think I can do it. I think I just need to stop.”

Matt said, “Well, how much have you written?” I said, “30,000 words.” He just said, “Everyone hates the 30,000 words stage.”

And it was that. And it was like sun came out, the birds started singing. It was like, “Oh, everyone hates the 30,000 words stage. This isn’t just mean being bad and awful and terrible and wrong.” And it’s that I think, that universality.

How to start writing? 41:20

Bec Evans: Let’s do some quick-fire questions because we’ve got lots that have come through in the chat. You said what you try to start and stay in the room. What do you do now?

Cathy Rentzenbrink: So I’m actually doing a new thing with a friend, which is where we sit on an open Zoom link with each other. Something about having her there means I don’t bolt. We’re mainly doing it for me because I’m a great bolter. So we’re mainly doing it for me, but she’s enjoying it as well. Although she can discipline herself and stay in the room, she’s benefiting it.

So I’m doing that on a schedule. We’re doing 10 till 12 and then, if available, we then have lunch with each other, again on Zoom in the kitchen. And there’s just something really nice and companionable about it. It takes the fear edge off for me. What I’m finding as well is I have to do the 10 till 12 with her, but earlier and earlier I’m basically turning up and just wanting to get going earlier and earlier. So that’s how I start.

Ways to stay in the room 42:32

Cathy Rentzenbrink: The rules for me are, this is the really important bit, I’m not allowed any other technology. I’m not allowed to look stuff up. I’m not allowed to convince myself, “Oh, maybe I’d better ask Bec about that event we’re doing tonight.” No Twitter, no whatever. I have my phone in case school ring, Matt’s fallen off a whatever, which happens quite a lot. But that’s the only reason I have my phone. I set my phone up so it has very little else on it and I’ve just trained myself to not look at other things. If I do that, then I just need to start and stay in the room. It’s controlling my access to other things.

Bec Evans: So much of our writing is about that environment, what triggers good or bad habits. And if other people like that idea of the Zoom, they should check out Focusmate. You can link up with anybody in the world. It’s a brilliant system. So if you haven’t got a writing buddy or you’re too scared to connect with somebody and ask for it, try Focusmate.

How do you manage self-doubt? 43:34

Bec Evans: How do you manage self-doubt? t’s a really big question. Just in a few seconds.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I just accept that it’s there. So it’s going to go away, but I’ve tamed it from a jabbering monkey sitting on my shoulder, sometimes to a lovely old Labrador lying under my feet. And if I put my feet on him, he even warms me up a bit. I did write a lot about this in my book, Write it All Down, with advice given to me by some therapist friends. So yeah, it’s a big subject, but there’s a measure of acceptance.

The paradox is, when I accept that writing is going to be difficult and not enjoyable, it somehow immediately becomes not difficult and more enjoyable.

Bec Evans: I found that when I was running the Arvon Writers Centre and meeting hundreds of writers. The successful ones weren’t the ones who had found ways, hadn’t found systems or had better habits. They were more able to live with the uncertainty. That’s what kept them going is they understood that it was part of the process and that they could continue to write with all of that going on. And that’s hard, that’s really hard. But there wasn’t a magic system. Acceptance makes a big difference.

How do you switch between projects? 44:57

Cathy Rentzenbrink: This question shone out at me. Trina, I think we’re soulmates and possibly our brains work the same way. “How do you switch between projects? I do this but very unsuccessfully. It’s like an excuse not to work on the other thing.”

Yes, yes, yes. It’s all those things. But what I’ve realised is, that’s fine. So if you have to have an excuse not to work on. If you need to feel you’re continually on the skive, that’s how you want to feel. I’ve realised I never really want to work on the thing I’m supposed to be working on. I always want to work on the skivey secret squirrel side project. So at the moment, I’ve got two books that I am finishing, I’m under contract for them, they need to exist. So I’m putting effort into those. But equally, I’ve got an ideas file, I’ve got mind maps everywhere of all the books I might write. I just capture it all.

And a bit like this morning when I woke up, don’t say no to the muse. So don’t say like, “Oh I just dreamed a new first line for the novel, but I’m not working on the novel now so I’m not allowed to listen to my dream.” So again, get yourself away from that slightly joyless, “How can I squeeze the most amount of word count out of myself?” And into the: “You know what? If I have to convince myself that if I only work when I’m skiving off from something else, I’ll just have another project.” And maybe you can trick yourself for a bit that the fake project is the real project, if you know what I mean. So trickery, trickery and laughs.

Dealing with feedback and rejection 46:20

Bec Evans: We’ve got a question about waiting for publishers and dealing with rejection. We’ve talked about doubt, which is our own feelings, and then rejection is when we get feedback from others. You’ve got some really good advice on writing for yourself and writing for others, and the vulnerability of those phases.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: Waiting to hear from publishers, waiting to hear from agents. But also then once you are published, waiting to hear whether, I don’t know, a retailer’s going to like your book or whether, “Oh, you’re down to the last three for Radio 4 book of the week.” But I’ve never been Radio 4 book of the week, so I don’t know who those other fuckers are that keep making it. Do you know what I mean? It’s just the point that it doesn’t stop.

You think that rejection will stop when you get published or get an agent, but actually it doesn’t. So you’re always waiting. So the thing I would offer you, and it’s again a bitter truth, is you might as well learn how to cope with rejection a bit because it will always be part of your writing life. And it doesn’t matter, I don’t think how successful you get.

I know writers who are much more successful than I am and they still find it very hard when they’ve just found out that the book that’s been optioned isn’t going to go to the next stage. It just is part of it.

I find it very difficult to deal with. I find it incredibly hard to deal with. I do think the advice to start something new.

Focus on what you can control 47:42

Cathy Rentzenbrink: It’s just think about what you can control and what you can’t control. I spend most of my life, not just my writing life, trying to put all my focus and attention into the thing I can control, and try to take my focus and attention out of the stuff that I can’t control. So now when I again publish a book, very anxiety-inducing, I just think of it as, “Right, I’ve got the book, tossing it into a little wooden boat, pushing it out to sea, and then the elements will do their thing.” Do you see what I mean?

To a certain extent as well, publishers agents do the same thing. Make it as good as you can, toss it into the boat, push it out to sea. This won’t be easy. Then just think, “Well, okay, I wanted to have something to a good enough stage that I felt ready to send it off to agents or publishers. I’ve done that, go me. How do I want to celebrate and what am I going to start? What’s my new thing going to be?” That’s what I would say about that.

Bec Evans: If people haven’t read Cathy’s, Write It All Down, it’s so full of encouragement and there’s so much advice about that starting phase and then going through that whole publication process. It’s described for memoirists, but all writers, I would say, would gain a huge amount of wisdom and comfort and very practical advice from that.

Cathy, we are out of time and I’m aware we haven’t answered all the questions. It’s just absolutely flown past. You have shared such insight into your own writing and into your writing room as well. That glimpse behind the screen, behind the page of what really goes on in your multiple books on all of your walls.

Wrapping it all up 49:35

Bec Evans: Is there anything you’d like to wrap up with? Is there anything you’d like to advise people?

Cathy Rentzenbrink: Just that I really do hope you do it. And again, do it anyway. So if it doesn’t get published, if it does get published but then you’re not book of the week on Radio four – all that stuff. What I hope is if there’s a parallel universe where I wrote my first book but it didn’t get published, which could very easily have happened, I really hope that the me in that universe knows that the most important thing is that I wrote the book and that I printed out and it’s over there in the corner of the room in one of those lever arch files.

That’s the most important thing and we can all have that. That’s not in the power of publishers and other people’s opinion. You might think and I would’ve thought this if I’d been listening to me back along, “Oh, it’s easy for you to say now that you’ve got that.” But when I got in a pickle a while ago, I can’t even remember when, I’m basically always in a pickle. It’s always much worse than I say publicly, because publicly I always feel quite good because I like Bec and I like all of you. I like being with people. It’s alone. That’s difficult for me.

So I always feel quite buoyant when I’m here. It can’t be that bad is what I think in the moment. But I got in a pickle a while ago and I fixed it by thinking, “Actually again, I’m now enslaved by the idea that if people don’t like this book, I won’t get another book deal. So this life will come crashing down and I’ll have to be a barmaid again. I’m now a bit old and I’ve got a bad back and I don’t know if I would want to put up with the men making comments about my breasts anymore, which I could cope with when I was in my early 20s but blah, blah, blah.” On and on and on and on.

I can always write 51:14

Cathy Rentzenbrink: I suddenly thought, “Actually, I can always write. The only thing that’s in the power of other people is whether I get paid to do it.”

That was just like, “Yeah, I’m going to write all my life. I’m going to be able to write all my life because I’m allowed to. No one can stop me and I’m going to do it all my life.” That’s what I would say. That’s what I would gift to you. If my next book doesn’t work and my next book is awful and if the novel doesn’t work out and nobody buys that one, nobody buys the next one, or this doesn’t work and I go mad and don’t manage to finish anything.

If I do finish them but nobody buys them so I don’t get another book deal, still, I’ll work out what to do, I’ll work out how to earn a living some other way and this will just be a peculiar window of being published in a much bigger life of writing. That I think is the way to cope with the idea of rejection of other people, of publishing.

Whatever your situation is, think of it as the publishing really is the smallest bit in what writing offers you and your life. And thank you all of you and Bec, because I have had a wonderful time.

Bec Evans: Well, thank you so much. If people want to hear more from Cathy, sign up to her newsletter. She’s occasionally on Twitter, she’s definitely on Instagram sharing lovely photos of daily swimming, which I would say is probably one of the most important routines of your writing life, actually, getting down to the sea most days. So yeah, so it’s cathyreadsbooks.com. Do check out all her books if you haven’t read them already.

I’m Bec, I am the co-author of Written: How to Keep Writing and Build a Habit That Lasts. You can find out all about me and Chris at prolifiko.com. I want to thank you all for your time and your energy and attention and showing up tonight and sharing your brilliant questions. It has been an absolute blast and I just love having proper honest conversations about what it’s really like writing. So thank you so much, Cathy.

Cathy Rentzenbrink: It’s a massive pleasure.

Bec Evans: Thank you.