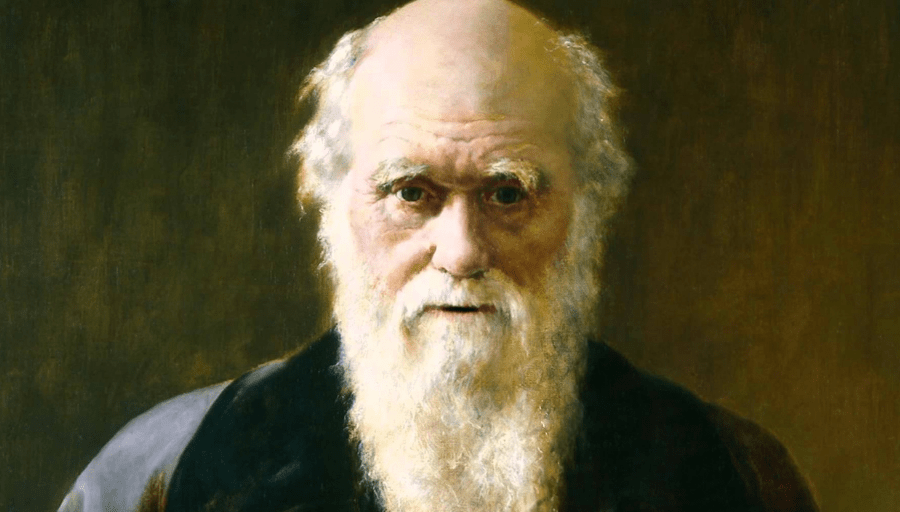

June the 18th 1858 should go down in history as the day when one of the world’s most influential, revolutionary books was finally sparked into life. On that day the English naturalist Charles Darwin – who was little known at the time – was opening his morning mail bag. He was about to get a nasty shock.

A friend returns

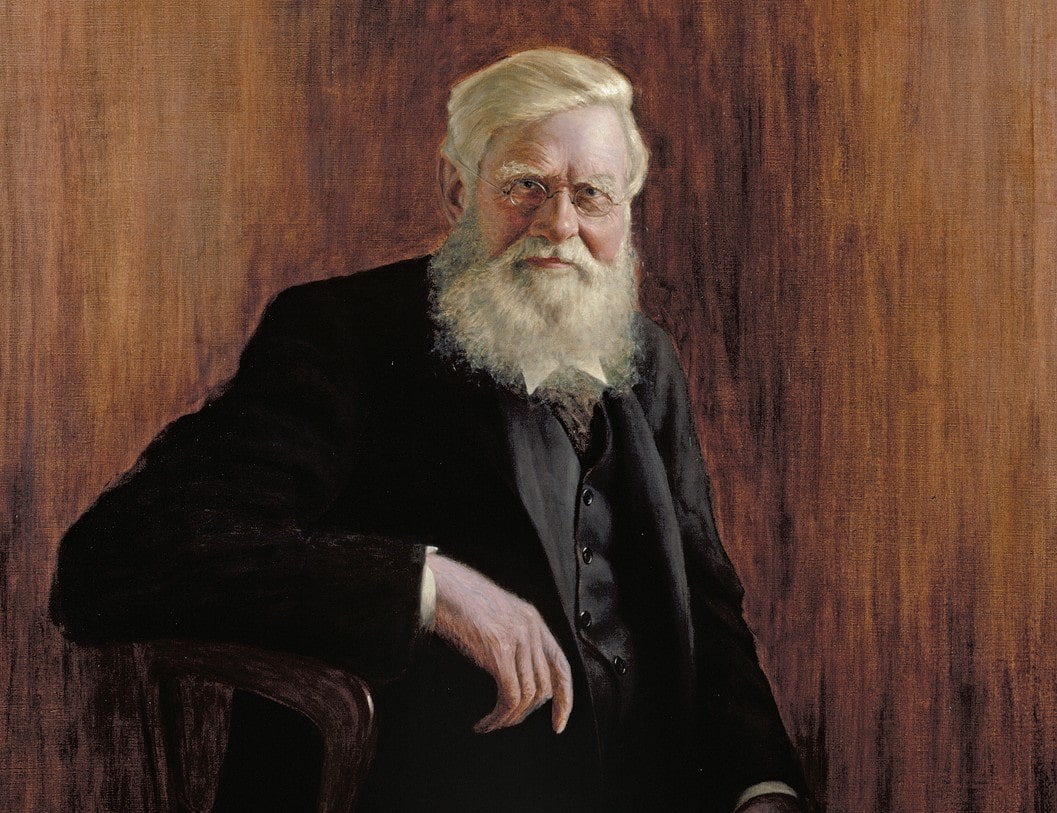

Darwin often exchanged letters with researchers in order to swap ideas, gossip and keep on top the latest thinking in his field. Today, he’d received a letter from his old mate Alfred Russel Wallace – a fellow naturalist – who’d sent him an essay he’d just finished. He’d just returned from the remote Indonesian island of Ternate where he’d been collecting specimens for study.

In the letter Wallace explained that he wanted to get the essay published but wanted Darwin’s help to do so as he was the better-connected scientist – which was true. Darwin had friends in high places – something that would come in handy later on.

In the letter he explained to Darwin that whilst on the island, he’d had a light bulb moment. He’d started to develop an intriguing, potentially game-changing theory – the subject of his essay. He knew it was Darwin’s field too so thought he would be interested. Wallace’s idea centred around his finding that members of the species with the most desirable characteristics appeared to be able to produce the best-adapted offspring.

The essay went on to describe in accurate, meticulously-researched detail how species changed over time. The exact same theory – the process of natural selection – that Darwin had thought up over 20 years ago and not revealed.

The clocks stopped

Can you imagine how Darwin must have felt first reading that letter? Decades of research and work – only for someone else to beat you to it. There he was in the dusty Victorian grandeur of Down House, his south of England residence, letter opener in hand. The clocks must have stopped. How the blood must have drained from his face.

Unknowingly, Wallace was planning to publish an essay on a topic that Darwin had made his life’s work – but had kept secret. Unfortunately for Wallace, he was asking help from the only person in the world with a vested interest in stopping him from publishing it.

In panic mode, Darwin blew the dust off his findings and dashed out an essay on his version of natural selection. Quickly, he rallied some wealthy and influential friends to pull strings at the prestigious Linnean Society of London – a learned biological gentleman’s club – to organise an event.

At the event, his paper and Wallace’s paper were both ‘read’ – the equivalent of a Victorian academic pitch-off – but as Darwin’s well-connected friends had arranged for his to be pitched first he gained first mover advantage. With the world’s scientific elite urging him on, Darwin finally finished and published On the Origin of the Species – and the rest is history.

>> Read more: How small steps lead to great progress

Darwin’s delay

The reasons why Darwin had only written half a book on the topic in over two decades and why he needed such a painful kick up his Victorian posterior to finish remain a mystery. It was hardly a lack of time. It wasn’t lack of access to resources or encouragement either – Darwin was a rich man with supportive friends. You’d never call him lazy.

In the intervening decades between his initial Galapagos field trip and publishing the results he kept extremely busy – perhaps too busy. He became a world-renowned scientific expert on barnacles, he earned a Royal Medal. He got really, really interested in earth worms. He studied South American geology, coral reefs, birds and flowers. He even edited a gardening magazine.

In his book Daily Rituals, journalist Mason Currey reveals that Darwin only ever divulged his secret theory of natural selection to a few close confidents telling one fellow scientist it was like “confessing a murder”. Could that fear have sparked such extreme anxiety, trepidation and procrastination that led him to sit on his research for so long?

Painting of Alfred Russel Wallace

Rooted deep

A reason why Darwin could have been so fearful of publishing could be rooted in his childhood – it often is. Before he set off on his voyage on the HMS Beagle in 1931 he was a Baptist, an avid church goer with very close friends in the clergy. He might even have been dubbed a creationist.

On the voyage, fellow researchers reported that Darwin openly claimed that the bible was factual. He considered it ‘history’ and never even doubted the literal fire and brimstone version of it. But on his return, he was a changed man. He was more sceptical and critical of religion and by 1849 he called himself an agnostic. His family would go to church every Sunday – but he’d stroll around outside.

With religion such a powerful influence in his early life, perhaps he was so reticent to publish because he knew his ideas would be like a tsunami hitting the church. He might have worried for his family – perhaps they might experience a backlash? And what would the impact be on his reputation? And then there’s always that nagging doubt. What if I’m wrong? Perhaps such extreme procrastination can be understood.

We don’t know for sure whether fear was behind Darwin’s gargantuan delay. But what we do know is that he suffered from very poor health for over 40 years with symptoms like ‘malaise’, tremors, headaches, exhaustion and severe tiredness. Symptoms that today would probably be called anxiety, stress and depression. Perhaps confessing ‘the murder’ weighed very heavy in his heart.

Thoroughly reptilian

Often called your ‘reptilian brain’, the Amygdala is one of the most primitive areas of your grey matter and it’s responsible for fear. It gets triggered when something threatening or unusual approaches. When something spooks your amygdala it releases chemicals into the brain which floods your nervous system with adrenaline and makes you take flight and run – or stay and square off against your opponent.

In general, that’s a good thing. It helps you protect yourself and it can stop you from taking unnecessary risks. But in other ways, it’s not so helpful – it is still triggered and makes us run and hide when you’re faced with less serious dangers and threats. But as psychologist Robert Maurer explains in his book One Small Step Can Change your Life: “The real problem with the amygdala and its fight or flight response today is that it sets off alarm bells whenever we want to make a departure from our usual, safe routines.”

>> Read more: How to stop procrastinating for good: a guide for writers

Feeling the fear

Writers often feel the fear when faced with their writing. What can make writing hard isn’t often that it’s technically difficult but rather because of all the mental baggage we carry round. Because of all the things that can swirl around your project like little black clouds – or in Darwin’s case, huge heavy rain-soaked cumuli nimbus. Normally, these things are deeply knotty and personal to you – often tied to your self-worth, personal confidence and they relate to the other things that are going on in your life.

Often, we’re scared of failure or public scrutiny – so we never start things. We fear we don’t have the talent to write – or might have lost it. We fear that the project is too much for us to take on or that someone else should be doing it rather than you. What these fears can result in is avoidance and when that happens – the amygdala has done its job helping us to avoid that particular stress – but it hasn’t done you any favours.

This fear is what makes us stop, delay, avoid, put off and procrastinate in a myriad of ways – cleaning, tidying, Twittering and more work, desk research or reading. Tasks that don’t feel like procrastination because they feel more like work – but they still are because they avoid us from doing the thing that we should be doing. The writing that challenges us.

In Darwin’s case his fear (and possible 20-year epic bout of procrastination) might have had deep roots in his psyche and triggered by the sheer magnitude of what he was about to reveal to the world – and who can blame him. Your fear might be triggered by something more prosaic (unless you are working on a world-changing idea – if so, please continue) but they are important to you and so, if you want to challenge your ancient monkey brain the way to do it is by tip toeing past it, keeping it small and reducing the stakes.

Don’t do a Darwin: 5 ways to reduce the writing stakes

- Keep it small: If your goal is too large – if you think about your project and feel overwhelmed in any way – it’s time to make it smaller. Ambition is good but not if it prevents you from doing any writing. It’s far better to produce a few small chunks of writing a few days a week that sit grim-faced at your desk for hours and not produce anything.

- Make it specific: If your project or the goal you’ve set yourself too vague or hard to grasp, this will make it more intimidating. The human brain likes clarity and finds it less threatening. ‘Write a novel’ a not a goal we can process very easily whereas ‘spend 30 minutes writing the introduction before the kids wake up and start annoying me’, is.

- Go one step at a time: When you have a very large goal it’s difficult to find a point of access. If you only focus on the next immediate activity you have to do this gives your writing (and your brain) more structure and clarity. Don’t think of the scary project itself, think about the next task you have to complete and do that.

- Dial-down the pressure: There’s a fine line between feeling excited by something and being intimidated by it. When ‘writing the book’ feels like an ominous, threatening task it’s time to start playing. Instead of ‘writing the book’ try some freewriting or journaling. Do a Pomodoro or two. Play around with some ideas – lighten the load and lower the stakes.

- Get away from your desk: Writing desks can be scary places – often loaded with guilt, pressure and sometimes, disappointment. If you get a sinking feeling when you open your laptop or approach your desk – don’t. At least for now. Make getting started easy – go easy on yourself. Grab a nice drink, go into the garden, sit on the sofa, find a nice spot that feels less pressured.