‘How to build a writing habit’ is clickbait for writers. Habits are a magic bullet to kill procrastination and end struggles with willpower. But beware! Writing does not meet the scientific definition of a habit so striving for the gold standard will end in failure. However, understanding how habits are formed can you set up a routine that will keep you writing long term.

Ancient Greek philosopher Epictetus said that: “every habit and faculty is maintained and increased by the corresponding actions: the habit of walking by walking, the habit of running by running. If you would be a good reader, read; if a writer, write.”

It’s a simple and compelling argument: if you want to become a good writer, then all you have to do is write, repeatedly. Yet many of us struggle to form a habit of writing.

While repetition might be the outward sign of a habit, psychology has revealed what goes on underneath. A couple of millennia on from Epictetus, research explains why writing is so tricky to do repeatedly.

>> Read more: Writing systems: finding yours, why it matters

What is a habit?

A habit is a behavior which, through repetition, becomes automatic. According to habits researcher Professor Wendy Wood, habits are a learning mechanism. Through getting a reward for repeating something we can learn and develop new habits.

We are “bundles of habits” William James, The Principles of Psychology, 1890

Woods’s research found that 43% of what people do every single day is repeated in the same context, usually while they are thinking about something else. She said that people are: “automatically responding without really making decisions. And that’s what a habit is. A habit is a sort of a mental shortcut to repeat what we did in the past that worked for us and got us some reward.”

Habits are performed with little or no conscious thought, they are by definition automatic, more of a reflex than a choice.

The foundation of habit formation

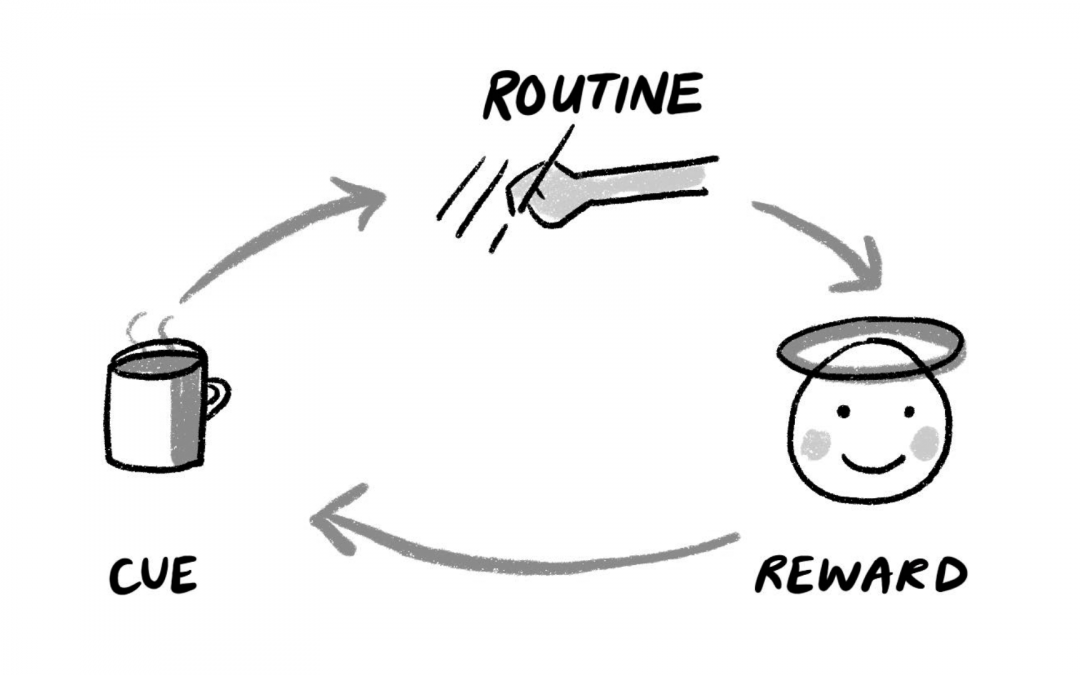

The pattern or mental shortcut behind every habit (both good and bad) was popularised by Charles Duhigg in The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do and How to Change as a three-step loop. He said:

“First, there is a cue, a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. Then there is a routine, which can be physical or mental or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.”

The more this loop is repeated, cycling through cue–routine–reward, it becomes ingrained and over time it is fully automatic, in short the routine becomes habitual.

“Over time a habit is born.” Charles Duhigg

Can writing ever be a habit?

Habits can transform our lives, they are the solution to our struggles. They are full of promise – habits are learned; our behavior can change, we can stop bad habits (procrastinating with Twitter) and build good habits (such as writing 500 words every day). The research not only proves this but shows us how.

Why then do most attempts to change fail?

Behavior change author Nir Eyal explains why some activities can never become habitual. He said: “Some routines can become habits but only if it’s a behavior that can be done with little conscious thought. Trying to turn a behavior that requires a lot of effort (like writing or breaking a physical fitness record) into a habit will backfire if you expect it to become effortless.”

Writing, unfortunately, falls into that category. Routines, like habits, are behaviours frequently repeated. However, unlike a habit, routines are not unconscious, they require some deliberate thought. Eyal proposes a test to check whether something is a habit: if the behavior can be easily skipped or forgotten then it’s a more likely to be routine than a habit.

>> Read more: How small steps lead to great progress

How to use the habit loop for writing

Writing can be hard, especially when you start out or begin a new project. Even when you are feeling motivated, it takes time, effort and willpower to get going. And to keep going writing requires grit and persistence.

But before you dismiss habits as an unattainable goal, you can learn from their formation. While it might not achieve the gold standard of an automatic behavior it can make your writing routine less stressful and more rewarding.

The habit loop is a simple neurological process at the core of every habit. It comprises three elements: the cue, the routine and the reward. Understanding the role of each element in the loop can help you set up writing, making it more likely that you do it; and using rewards will associate pleasure with the task, making repetition more probable.

Duhigg referred to the habit loop as “a framework for understanding how habits work and a guide to experimenting with how they might change.” We’re big fans of experimentation at Prolifiko and advise the writers we coach to run experiments as they figure out what helps them to write.

Charles Duhigg’s 4 steps to explore the habit loop

1. Identify the routine

The routine is the behaviour. As you are reading this blog you’re probably interested in developing your writing.

Take time to consider what a writing routine might look like. When do you want to write, where, what will you do when you show up each day? Imagine it fully – visualise, make notes on what is involved in a successful routine.

“Routine is a condition of survival” Flannery O’Connor

2. Experiment with rewards

The reward embeds a routine. It taps into the reward circuitry of the brain to associate something pleasurable with the behavior as you complete the first loop, making more likely you will re-do the loop in the future. As such, it is a reinforcer that increases the probability the behavior will happen again.

In neuroscience rewards have a very specific function and fulfil narrow criteria. For the habit loop to work, the reward must be delivered either during the routine or milliseconds afterwards. In that instant, dopamine is released in the reward centre of the brain, processed, and new neural pathways are formed that will embed the habit.

>> Read more: How to keep writing using rewards

Stanford researcher, BJ Fogg, and father of Tiny Habits offers advice for finding that immediate celebration. We take inspiration from his maxim: “People change best by feeling good, not by feeling bad.”

He’s right. However, if you are struggling to design the perfect dopamine-kick for your habit, relax. Step back and look at your writing routine and find ways to make it more pleasurable. It’s hearsay in habits circles, but think of treats or incentives rather than immediate rewards.

Consider what will generate positive feelings as you write. How can you treat yourself after writing? If you need an incentive to bribe good behavior what does that look like?

Have fun experimenting with rewards, give yourself something to look forward to at the end of a writing session. One trick we suggest is to use your common procrastination activities as rewards rather than delaying tactics. In short – Instagram after writing not before!

“I must write each day without fail, not so much for the success of the work, as in order not to get out of my routine.” Leo Tolstoy

3. Isolate the cue to write

The cue sets up the routine. It’s a trigger to action, prompting behaviours you want to do and other times triggering unwanted behaviours.

Duhigg found that almost all cues fit into one of five categories. These can be used to break bad habits and trigger new ones.

- Location – where do you want to write? We’re currently in the Covid-19 pandemic when many of us are working from home. Can you find a space to write that’s different from your work space? If you are spending most of your working hours around the same kitchen table how can you change it to suit different activities? Clearing it between work, eating and writing can help, but also think of setting up cues, such as putting out your notebook or lighting a candle.

- Time – at what time do you want to write? Are you an early bird or an owl? Is there a time of day you are less likely to get distracted?

- Emotional state – how you feel affects your behaviour. Take a cue from your emotional state to write. Use feelings to fuel your writing – if you’re frustrated with work, grab your notepad rather than send an angry email to your boss. Feeling great then free write and generate ideas. Celebrate life’s highs and get through the lows with writing.

- Other people – who can help you write? How can you find other writers to buddy up with? What about finding supporters to share your projects with? Think of readers, mentors, and creativity cheerleaders. Enlist others to trigger your writing, to learn from and also make it more fun.

- Immediately preceding – what action do you do beforehand? Attach writing to an activity you already do, for example doing morning pages as soon as you wake up, writing after you’ve eaten lunch, or before switching on Netflix. As a bonus, use a visual trigger to set it up, for example keep a notepad on my bedside table to trigger morning writing or set a notification or schedule writing time in your calendar.

4. Have a plan

It can take a while to establish a writing routine, and once you have one, they can be easily lost. Rather than rely on willpower you need a plan.

Once you’ve identified when and where you’ll write, then create plan – this is as simple as noting it down, for example: “I will write every week day at 8am for one hour at the café opposite the train station.”

This example is clear and specific, it uses an everyday activity like commuting to attach the new writing behavior to. It gives a time and regularity so it’s clear when it’s been achieved and has the bonus of building in a reward with hot coffee and cakes.

Bonus: the power of belief

You have set up your loop: you’ve cued the writing routine, chosen the reward and put in place a clear plan. Duhigg found one extra element to fix your routine. “for habits to permanently change, people must believe that change is possible. … Belief is easier when it occurs within a community.”

Writers have a tricky relationship with self-belief. Whether you’re starting out, have a publication pipeline, or backlist there’s always an opportunity for your inner critic to eat away at your confidence. So, having the support of others can give you a much-needed boost.

Join a community of writers. Find a group of like-minded people with the same goal as you – to write. Sign up for a writing group, join an online writers’ hour or Shut Up and Write!

If you’re feeling shy, start small, researchers found that having just one other person is enough to make you believe change is possible.

>> Read more: The complete guide to writing accountability – hold yourself to account and use others to help you achieve your writing goals

7 steps to build a writing routine

Many writers unwittingly fall into the ‘if only I had a writing habit’ trap and then blame themselves when they fail. According to the definition of a habit, it is impossible to write ‘unthinkingly’. However, by understanding how habits are formed you can trigger your writing, develop a routine, and keep going day after day.

As John Updike said, “A solid routine saves you from giving up.” If you want to get started and build a rock-solid writing routine, tap into the habits loop:

- Don’t beat yourself up for failing to create a habit. In behavior change habits have a very specific and narrow definition that makes it hard for writing to ever be unconscious and automatic.

- Instead, understand the habit loop and use psychology to help you design a writing routine.

- Identifying a cue to trigger your writing by exploring the 5 types of cue: location, time, emotional state, other people and activities you do beforehand.

- Experiment with rewards, incentives and treats to associate pleasure with writing and make you more likely to show up again.

- Create a clear plan so you know exactly what is involved, when and where you’ll write.

- Build a sense of belief that you can write by finding a community to support you.

- Change! The benefit of routines is that they can change, so embrace the loop to develop new, better, more fulfilling writing routines.

“I certainly have a routine, but the most important thing, when I look back over my career, has been the ability to change routines” Anne Rice