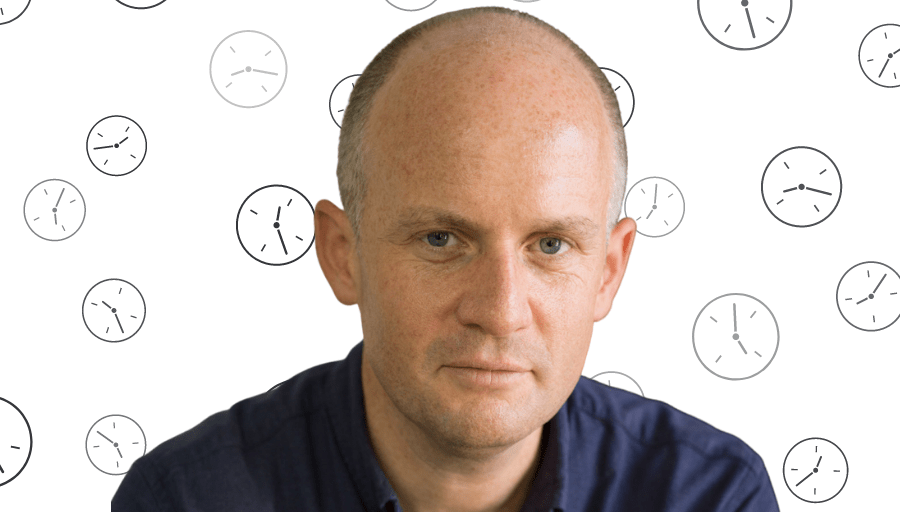

Oliver Burkeman’s new book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time and How to Use It explores how to build a life of creativity, productivity and meaning when we have limited time available – and even less control over that time. I caught up with him to ask what that means for how we live and how we write.

Time and how to use it

Writing a weekly productivity column for The Guardian, self-confessed productivity geek, Oliver Burkeman likened himself to an alcoholic employed as a wine expert. He realised that getting more done just made him more stressed and unhappy so he turned to ancient and contemporary philosophers, psychologists, spiritual teachers to better understand how to live. Four Thousand Weeks: Time and How to Use It shares what he learnt about leading a fulfilling and meaningfully productive life.

Productivity is personal

The problem with a lot of productivity advice, said Burkeman, “is how much of the given piece of advice is good, versus that person has the right personality for it?”

I find this a comfort. Because we are all different we don’t have to attain the one, gold standard, approved, best way of doing things. Accepting this takes the pressure off you to conform to the myth of a creative genius. Instead, when figuring out what works for your life and writing, start with you, your life, your personality and preferences.

I was keen to find out what this means for his writing. In a follow up to my 2014 interview, Oliver Burkeman shares his take on how to write when time is limited.

“I’m an expert in a very amateur way – I’m vacuuming up all the research and testing it out with a sample size of exactly one. I stumble through in trial and error, so to some extent I can say I have figured some things out.” Oliver Burkeman

Oliver Burkeman’s tips on writing when time is limited

1. Do a few things that matter to you

A lot of productivity advice promises that soon you’re going to become limitlessly capable of doing everything you need to do: to produce perfect work, to be able to deal with every incoming demand, to get round to every goal and satisfy every person.

That’s systematically, inherently impossible. It’s not because you didn’t find the right technique. It’s not because you haven’t put enough elbow grease into it.

Once you see that that ship has sailed, it’s great. That huge super-structure of pointless stress, lifts away from you, and you can just do a few things that matter to you.

2. Limit the things on your to-do list

I think that a lot of us spend a lot of our time demanding impossible things from ourselves and becoming paralysed in the process. If you were just going to wake up in the morning and pick from all the opportunities, it’s unmanageable.

What I try to do is funnel through work-in-progress where I only allow 10 things. The goal is you’ve just got 10. That narrows your focus a bit. Narrowing it to one item would be hopelessly unrealistic, because you need to bounce around a bit, you need to take care of different life domains. And then once I’ve done a few, and the number’s gone down to six, then bring four more in. It’s not flawless, because you can still use it to just keep turning over three or four easy tasks, but it’s mainly working.

>> Read more: How to make time to write – 4 approaches to finding time in busy schedules

3. Do one thing at a time

When I’m really in a rut, I then follow some version of this technique where you literally write down an action on a notebook.

Do it, cross it out, write down the next one. Do it, cross it out.

You’re taking yourself by the hand and telling yourself: “Okay, we’re just going to do one thing.” It’s so gentle and the time horizon is just literally the next five minutes. And of course you can chain together a whole career that way. That’s all you’re ever actually doing is one action after another, right?

4. You already have enough to write

Writing is based on things that you’ve already written. It’s based on ideas that you’ve been reading about, things you’ve been talking about with your friends at the park or the pub, and the things you’ve been thinking in the shower.

In other words, the answer isn’t that you have to become some kind of genius who can sit down and summon brand new ideas into being.

5. Hold on to the ideas you have

I don’t think there’s such a thing as a brand new idea.

You just have to have personal systems that allow you to keep track of all the ideas you’re already having and already encountering in your life. Carry a notebook everywhere you go, save all these articles you discover when you’re browsing online.

Create a moment in your daily or weekly routine where you take all these scraps of paper that you’ve been writing ideas on, or the notebook that you’ve kept in your pocket, and put them all into a file to keep track of them. Then all you need to do when it’s time to is to take what you’ve got and work with it.

6. Write little and often

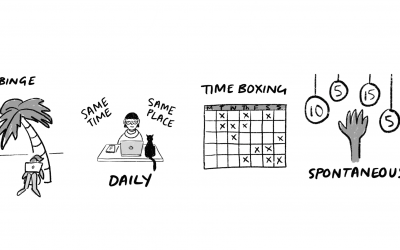

Confronting limitation is about understanding how true it is for almost all writers that little and often is the better path to a productive output than writing in binges.

Again, if you’re a binge writer and you work for days at a time and it works for you, don’t let me stop you. But I think for most people it doesn’t work or it works for three days, and it puts you out of action for a month, which is another way of saying it doesn’t work.

I suggest working in small amounts. Aim only to do half an hour or an hour in a day, maybe a little bit more depending on whether you’re combining it with a day job, but not very much.

7. Stop when your time is up

It took me a while to learn that you also have to stop when your time is up, even if you feel like you’re on a roll and you can continue. It’s all about ignoring that voice in your head that says, “I’ve written 700 words, so why don’t I try to write 3,000 today? That will be amazing.”

Every time you resist that voice, you’re building a muscle, building a capacity for patience, for coming back to the job day after day after day which will lead to much more writing because it will make you feel more excited about getting down to that work and not like writing is something you flog yourself to death on.

>> Read more: Why the fixed schedule productivity approach to writing will give you more downtime

8. Writing is hard – but you can handle it

Writing, or creative work in general, often feels quite difficult. It’s uncomfortable to do it. It’s kind of hard. It makes you feel a bit grouchy.

I think this is another way in which we deny our limitations. We think that if we really knew what we were doing, it would feel totally lovely to be doing it. We’d be in a constant state of flow and therefore, if that’s not how it feels, well, we must have writer’s block. We must just not have the skills that we need to write.

You get into this double-bind where like writing feels like a problem, which it is, but it also feels like it’s a problem that it feels like a problem, which it isn’t.

It’s uncomfortable, but you can totally handle that discomfort. You don’t need to try to power through it and make it go away. You can just say, “Okay, I feel reluctant about doing this. I didn’t particularly want to do it. It feels difficult and I’m going to do it at the same time.”

9. Overcome your discomfort by setting tiny goals

The prospect of this kind of discomfort will stop you doing things for days and weeks and years on end.

Then, it’s consistently mind-blowing how almost all the time, it isn’t a big deal to go through that discomfort. You have to learn this lesson over and over and over again.

That’s another very good reason for these tiny goals and writing in tight bursts is that it gets harder and harder to fool yourself that you can’t cope with that discomfort, because actually 10 minutes of discomfort, you can cope with.

>> Read more: How small steps lead to great progress

10. Procrastination and feeling in control

I’ve often assumed that the next thing would be incredibly hard or scary, and that’s a good reason to procrastinate. I’ve definitely procrastinated on all the book work that I’ve done.

But when you actually get into it, the experience doesn’t justify the anxiety you had about it. Part of the reason that feeling anxious and procrastinating on things is because they boost the feeling of control. If you don’t start something, you’re still in the driver’s seat.

I think most of us will do anything to avoid that lack of control. Because it’s like jumping off the diving board where you don’t know what’s going to happen.

11. The fantasy of perfection

A lot of people are fixed in these perfectionistic ideas, where the moment you start doing 10 minutes that’s not very good on your manuscript – that’s the moment at which you’ve had to wave goodbye to doing five hours a day and it all being Tolstoy quality.

I mean, you can hang onto that thought as long as you don’t start. As long as your finitude doesn’t come into act or contact with the world and you start doing things, you can hang onto the greatest fantasies about how it’s going to be.

12. Reject what doesn’t work

There’s this whole culture of goal-setting which is to use the ambitiousness of the goal to drive to ever greater heights and that has never worked for me.

I never get round to implementing Cal Newport style annual goals. It’s not that I disagree with them. But I have to say, it never quite works out for me. It’s never the way I actually seem to break the most ground.

13. Do what works

All the useful productivity stuff that’s ever worked for me and that continues to work is just about coming up with a slightly wiser answer to the question: “What shall I do right now?” And it’s feeling slightly more motivated and enthusiastic about what shall I do right now.

That idea of just writing a single thing and crossing it out, that’s the sort of most basic expression of “what do I do now?”

14. The game changer: Finish it!

And then the other thing I try to do a lot is to limit work in progress so that there’s a fixed number of things that I’m working on right now and that I will finish one of them or abandon it before I bring in another one.

As and when I manage to motivate myself to do three or four hours of serious creative work, it’s going to be on the same thing for two or three days, until that’s done.

That’s a game-changer. Because otherwise what happens is the moment any project feels a little bit difficult, you just bounce off to another project and you never make serious progress on any of them.

“Done is better than perfect,” relates to this idea that 100 words that you write are better than 10,000 words that you think about writing one day. One thing done is better than 10 things not getting very far.

What I’m doing when I launch into 10 projects at once is fundamentally fuelling my sense of being unlimited or godlike. Busyness can do that sometimes. On some level you’re thinking, “Hey I’m in demand. I’ve got all these things going on, that’s great.” But it’s actually a way of hiding from picking one of them, putting it on the table in front of you and doing that thing.

>> Read more: The complete guide to writing accountability – hold yourself to account and use others to help you achieve your writing goals

15. From systems to success

Make sure that you have, in your own life and work, the personal systems that allow you to keep having and developing ideas, writing words, and sending those words out into the world. What happens then is you gradually expand the perimeter of your reach, and as that perimeter expands, you sort of bump into more of the opportunities that might lead to greatest success.

***

Four Thousand Weeks – Time and How to Use It by Oliver Burkeman

I loved talking to Oliver Burkeman and finding out his advice on how to live and how to write and encourage you to read his book for more wisdom.

Four Thousand Weeks: Time and How to Use It explores how to build a life of creativity, productivity and meaning when we have limited time available – and even less control over that time. The 4,000 weeks of the title is the equivalent to 80 years of life. It’s a number we can all relate to and helps us understand our finitude (a rather nice euphemism for death). That is not reason for despair but, Burkeman argues, a liberating concept. Accepting our limited time on earth allows us to leverage the possibilities and opportunities we have. In short, confronting our own death is the key to leading a fulfilling and meaningfully productive life. And of course, and writing more.

Sign up to his newsletter The Imperfectionist, check out his other books, and read our previous interview with him: Oliver Burkeman’s 10 tips for a productive and happy writing life.

[et_bloom_inline optin_id=optin_7]