What-if thinking is a powerful tool for writers. It helps novelists create new worlds to shine a light on how we live now. Speculating about the future is not just the preserve of science fiction writers – it can be helpful for all writers as they plan their writing goals and habits. It starts by telling stories about future you.

Margaret Atwood wrote: “Stories about the future always have a what if premise, and The Handmaid’s Tale has several.” Atwood’s work is part of a rich tradition of speculative writing, taking a prompt from ‘what if?’ to generate works of art and fiction.

In Ancient Greece Euripides created what-if tragedies like Medea, hundreds of years later, Shakespeare imagined if-only fairyland comedies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In the 20th Century writers grappled with some of the biggest moments in history imagining the opposite: What if Hitler won the Second World War led to Philip K. Dick writing The Man in the High Castle and Malorie Blackman reversed racial power structures in her Noughts and Crosses trilogy.

Imagining outcomes counter to the facts, i.e. counterfactual thinking, can be helpful for all writers. Not just as a creativity prompt but applied to our own lives. It helps us imagine possible futures and can be a psychologically sound way to plan and build new habits and behaviours.

>> Read more: All good things must begin: how visualising success helps writers

Counterfactual thinking

Counterfactual thinking is a tendency we all have to create possible alternatives to events that have already happened. According to research, these thoughts consist of ‘What if…’ and ‘If only…’.

Daniel Pink explores counterfactuals in his book Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward. He describes two broad categories of counterfactual:

- upwards where you imagine how things could have been better, and

- downwards where you imagine how things could be worse.

Imagining how things could be worse, makes us feel better now. That’s great! However it doesn’t lead to any change. To start a process of change we actually need to lean into upward counterfactuals, the ‘if only’ thinking, that makes us feel bad.

How counterfactuals help us change

One analysis of research found that “counterfactuals produce negative affective consequences.” While this make us feel miserable, it concluded that “the net effect of counterfactual thinking is beneficial.” Sitting with the discomfort of regret can support us to change for the better.

Pink’s deep dive into the research on regret shows how we can harness the ‘if only’ of upward counterfactuals to change. That’s because while dwelling on the negative consequences of earlier actions makes us feel bad, it helps us strive to do better. If only I practised my reverse parking, then I wouldn’t have failed my driving test first time. That failure led me to double down on my manoeuvres, sail through my second test, and I believe makes me a better driver now. Let’s look at some writing regrets.

Lean into regret

I regret not taking a writing class when I was in my early-twenties and working in a bookshop with oodles of spare time – time that I dedicated going to the pub with my co-workers. If only I’d learnt some craft then, I’d be a better writer now!

The key to change is to not ignore or wallow, but to lean into it. As Pink says: “We feel worse, but do better. We do better in part because we feel worse. And so that’s one of the things that regret does for us.”

>> Read more: Say it, write it, draw it – 8 visualising exercises for writers

As the much-quoted proverb says: The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now. So while I regret missing out on decades to practice writing skills I’d learnt when younger, I can’t change the past. But I can act now, which is why I’ve booked myself onto a year-long fiction masterclass starting this month. Rather than wallowing over the lost time, I’ve turned my regret into action. As Pink argues, I feel worse but do better.

The neuroscience of change

Counterfactual thinking helps us to revaluate the past and make plans for the future. That process starts in the brain.

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to change. Our experiences, actions and thoughts create new neural networks. With repetition these networks are reinforced and become stronger – which is why people often refer to the brain as being like a muscle. It isn’t a muscle* but the analogy is helpful and explains why some habits (usually bad ones) are so strong they feel impossible to break.

Neuroscientist Dr Gabija Toleikyte has a brilliant exercise that primes our brains for change. It works for writing and all areas of life. I use this exercise myself when I get stuck, need to set new goals or renew my intention. We’ve also used it with lots of different writers, which led to some fascinating observations on brain plasticity and mood.

Prime your brain for change

To do the exercise, grab a pen and piece of paper, sit somewhere comfy and quiet, and imagine your writing goal. Take time to visualise that goal, what you are aiming towards, what the output or outcome will be: a first draft, a completed novel or thesis, a collection of essays or stories. Make a few notes about that goal so you have something to explore.

Let’s time travel into that future. We’re going to exercise our counterfactual thinking with both sides of what-if. First, what if you worked on your goal and achieved everything your dreamt of? Next you’ll take the opposite position, what if you didn’t work towards that goal and didn’t achieve it?

- On your piece of paper, draw a line down the middle. On one side write BENEFITS of working on your goal and on the other write DOWNSIDES of not doing it.

- You are going to write 50 benefits and downsides. Yep, that’s right, 50 – having an exhaustively, long list gets the brain fired up and all those neural networks connecting.

- If you need a prompt, Dr Toleikyte suggests using the 8 main areas of your life, these are your: work, family, romantic relationships, social life, hobbies, physical health, mental health, personal growth / spiritual practice.

- Project yourself into the future, visualise fully both of these scenarios: how you will feel when you have successfully built a new habit, changed your behaviour and reached your goal; how will you feel when you have failed to.

Brain plasticity in action

If you do this exercise it will have an effect on your mood That’s what I experienced personally and also when I did this with other writers in workshops and during supported coaching sessions.

>> Read more: How to set a writing goal: the ultimate guide

Imagining a positive outcome, such as what it’s like to achieve a long-held goal, it feels good because it triggers lots of happy-making brain chemicals. Likewise, imagining a negative outcome sucks. While the thought might be imaginary, what is going on in the brain is real, observable neurochemical reactions. Thinking about doing something causes new neural pathways to emerge. It’s neuroplasticity in action, with the visualisation creating and changing neural networks and priming us for action.

Being the sort of Pollyanna positive person I am, I often stick to the 50 benefits exercise and avoid doing the downsides. I don’t like feeling bad and I don’t like making other people feel bad. Doing this in workshops led to a palpable black cloud in the room as people’s moods plummeted. But in avoiding the downsides doing I was missing out on the power of regret.

The power of regret for inspiring change

As Daniel Pink says, regret is a “uniquely painful and uniquely human emotion” because it involves us blaming ourselves for doing, or not doing, certain things in our lives. His survey of nearly 5,000 Americans found that respondents overwhelmingly regretted things they didn’t docompared to those they did by more than three to one.

He goes on to say that the fact that we experience regret can make us better in the end. Regrets shape our future, and sometimes even the very thought of having one is enough to spur us into action and make radical changes to our lives. So while imaging future failure, feels bad, it can help us make changes now.

Conversely, all those warm fuzzy feelings of success when we imagine a positive outcome can led to inaction. Research by Dr Gabriele Oettingen in her book Rethinking Positive Thinking: Inside the new science of motivation found that imagining positive visions of future success calms your breathing and heartrate, and this can lead you to feeling like you have already achieved your goal.

If you actually want to achieve your goal, rather than just feel it, you need to take action, identify a first step and do it.

Start by exploring your what-ifs then take steps to harness the power of regret.

>> Read more: Steps, scaffolding and serialisations – how sub-goals keep you writing

***

Postscript: while I do regret not taking a writing class when I was young, carefree, and blessed with lots of time and zero responsibilities, I am also very grateful for my time in the pub with my bookshop colleagues, one of whom was called Chris. Long story short: we fell in love, got married, and twenty years on wrote a book together.

Further reading and references:

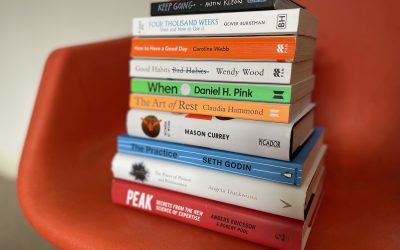

- Daniel Pink Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward

- Dr Gabija Toleikyte Why the F*ck Can’t I Change?

- Dr Gabriele Oettingen Rethinking Positive Thinking: Inside the new science of motivation

* Not only is the brain not a muscle, it is happens to be the fattiest organ in the body with 60% fat, it also demands a huge amount of energy when doing cognitive functions like writing, so when you get stuck, feed your brain.

[et_bloom_inline optin_id=optin_7]