If you feel 100% sure that the writing project you’re working on is the best (or the worst) thing you’ve ever done: you’re wrong. Research says the only thing you can ever know for certain is that keeping going – being prolific – is best thing to do.

Hits and misses

Everyone loves dear old Winnie the Pooh. Everyone that is, aside from the forgetful bear’s creator A.A. Milne who couldn’t stand the sight of him.

Milne could never understand why his books for kids were so popular – he grew to hate them. He thought the three novels, four screenplays and 18 plays he wrote for adults were way better.

I don’t know about you, but I didn’t even know A.A Milne wrote any adult fiction (sorry A.A Milne).

When Woody Allen finished Manhattan – arguably his best and most popular film – he asked movie company United Artists to scrap it. In fact, he was so sure that it would be an embarrassing flop that he offered to give United his next film for free on condition that Manhattan was left on the cutting room floor. Happily, they refused.

Once he’d finished a novel, Kurt Vonnegut used to give his writing a grade (he was an ex-teacher after all). Whilst some of his popular books did get good marks, others like the best selling Breakfast of Champions get a D whilst his worst selling books, like Jailbird get an A++.

All this is not uncommon.

One of the attributes of creative people says Prof. Dean Simonton – a University of California academic who’s been researching creativity for over 40 years – is that they have an extraordinarily poor sense of whether the thing they’re creating, inventing or making is any ‘good’ or not.

>> Read more: Why mastery matters and writers should push themselves

Mess or masterpiece?

In fact, Simonton thinks that it’s virtually impossible for anyone involved in a creative project to know for sure whether they’re making a masterpiece – or just a mess.

And when they do feel 100% sure – they invariably get it wrong.

In one study, Simonton tracked the creative output of ten famous composers over their lives. He wanted to understand the factors influencing them to make great work.

He writes about composers like Handel who pinned all his hopes on a few operas that nobody other than him ever really liked. He also writes about Beethoven who predicted incorrectly time and time again which of his symphonies and sonatas would catch on with his audiences.

In general, Simonton found that the composers themselves were completely oblivious as to which of their pieces were going to be masterworks – and which would be flops.

He also found it didn’t really matter how much effort (or not) a composer put into a particular piece of work or how quickly they dashed it off.

“When a composer descends to produce a rash of ‘pot boilers’ or ‘pieces d’occasion’ for monetary or promotional gains, the production of masterpieces is not sacrificed. This finding raises the issue of whether the creative genius has much capacity to discern between major and minor works. Only posterity can make the final judgement.” – Dean Simonton

His research found no specific patterns as to when these composers reached their creative peak either. Some had huge successes early on, then experienced long barren periods then big wins at the end of their lives. Others produced classics like clockwork throughout their lives.

Some composers composed during times of severe civil unrest, others whilst seriously ill, or at times of family break ups. Still, nothing really influenced how many major works they produced – or not.

>> Read more: How to stop procrastinating for good: a guide for writers

Do the one thing that matters – being prolific

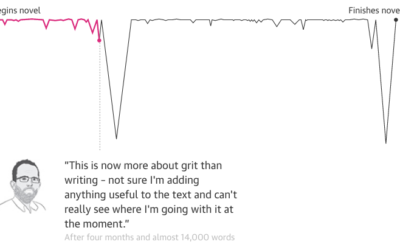

In fact, Simonton finds there’s only one sure-fire indicator of future greatness and that is how many works in total a composer had produced – both the good and the bad – throughout their lives.

“Each creator is impotent to improve their chances of success with increased skill or maturity. The creative genius seems unable to determine which works will earn future applause. All the creator can confidently do is to exploit the odds by being productive.” – Dean Simonton

Simonton found that external and internal influences like history, geography, age, ability, illness, wars, famine, aptitude or talent had zero bearing on how successful or otherwise these composers were.

He found the only factor to career success was how productive or otherwise people were. These people kept going through thick and thin – and that’s what make them great.

So, to the (highly predictable) moral of the story.

Trying hard, being committed and working like a Trojan is what many creative people do. And should be applauded for doing.

But research finds that trying too hard to ‘be a writer’ or ‘be a composer’ isn’t what makes you great.

What makes you great is doing – being productive, writing stuff, making stuff – keeping going.

And in the end, that’s the only thing you’ll ever know for certain actually works.