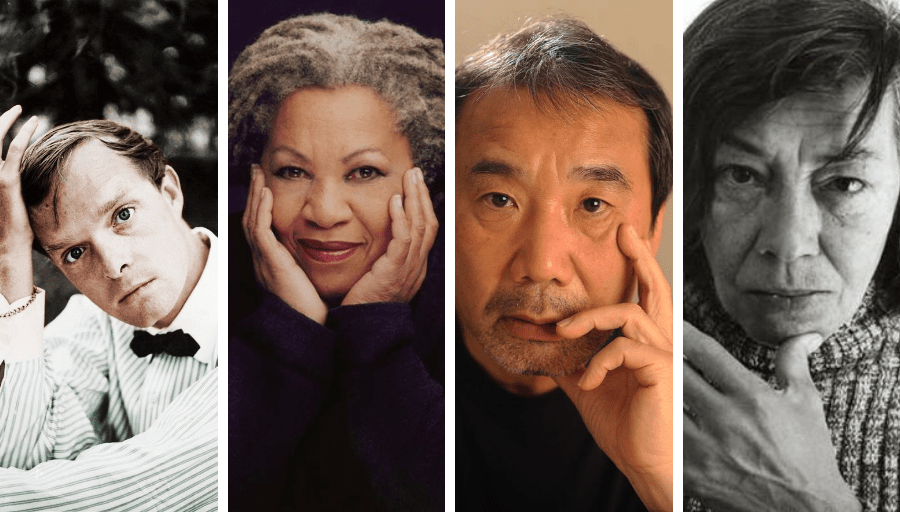

In Daily Rituals Mason Currey provides glimpses into how some of the greatest minds use their time to produce exceptional works. We set out to spot trends and commonalities in their idiosyncrasies, here’s four things all writers can learn.

Currey collects snippets of the routines and habits of 161 creatives including writers, painters, composers, scientists, directors and philosophers. I read the book in an attempt to spot any trends and commonalities in their idiosyncrasies. This turned out to be a very entertaining process (‘quirky’ doesn’t always cut it for some of these talents) and it produced results likely to interest both established and would-be writers.

What the book shows, amongst other things, is that most creatives follow a more or less strict schedule designed to accommodate their personal idiosyncrasies. Having identified what works best for them, they are successful in translating their talent into concrete work because they are able to remain flexible and adapt their routine to changes in their circumstances over time.

>> Read more: Daily rituals and quirky habits: Q&A with writer Mason Currey

There are many examples of this in the book, but by going deeper one can find even more trends shared, in particular, by writers. Here are four of them:

1. They know what puts them in the right headspace to write

No, writing isn’t always easy and it isn’t always pleasurable, either. William Styron famously told The Paris Review “Let’s face it, writing is hell”. The novelist and essayist felt good about his writing when it was going well, but struggled with getting started each day and music was his way to transition into ‘work mode’.

Being aware of what makes you want to write can make the difference between making the most of that day off you have and procrastinating because you can’t get into the ‘right mood’. Some writers can just get up and start writing, but others need ways to ‘ease themselves’ into it and to enter that ‘deep focus’ zone.

For Patricia Highsmith, it was all about making the act of writing as pleasurable as possible by avoiding any sense of discipline. She achieved this by sitting on her bed surrounded by cigarettes, ashtray, matches, a mug of coffee, a doughnut, sugar, and a strong drink. The playwright Tom Stoppard once said that, for him, only fear can be a catalyst for writing; for the American novelist William Gass it was anger. The 18th century German poet Friedrich Schiller kept a drawer full of rotting apples in his workroom maintaining that their decaying smell gave him the urge to write. To each their own.

“For Patricia Highsmith, it was all about making the act of writing as pleasurable as possible by avoiding any sense of discipline”

Toni Morrison allegedly said: “Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they expect to make the contact, where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process.” She likes to make coffee and “watch the light come” when she gets up early to write. Everyone has something, you just have to find what works for you.

2. They pursue other activities alongside their writing

If you have ever seen Tim Harford’s Ted Talk on slow-motion multi-tasking, you’ll know where this one is heading. Having multiple projects on the go that you devote time and effort to, more or less regularly, can be highly beneficial to your creative outputs, and it’s very popular among writers, too.

“Having multiple projects on the go that you devote time and effort to, can be highly beneficial to your creative outputs.”

Both Henry Green and Wallace Stevens kept their full-time day job throughout their writing career, finding that it provided much-needed structure to their day and freed their creative mind from money worries. Herman Melville liked to work in the fields of his Massachusetts farm to relieve stress after a full day of writing. Vladimir Nabokov liked to chase butterflies on the Alps in the summer, often hiking over fifteen miles a day. Patricia Highsmith bred snails, eventually keeping three hundred of them in her garden in Suffolk and smuggling them to France when she moved. William Gass goes out to photograph the derelict parts of the city for a couple of hours most days before he sits down to write.

Moving between projects according to mood can provide a much-needed break and the opportunity to look at problems from a different angle―particularly helpful if suffering from writer’s block. Ultimately, having a ‘serious hobby’ alongside your writing efforts can provide much more than a comprehensive butterfly collection.

>> Read more: The surprising creative hobbies of superstar scholars – and what you can learn

3. They don’t like relying on inspiration

Most writers swear by a regular―often daily―writing routine as an antidote to the fickleness of inspiration.

The American novelist John Updike believed that a solid routine is what saves the writer from giving up. In a 1978 interview, he said: “I’ve never believed that one should wait until one is inspired because I think that the pleasures of not writing are so great that if you ever start indulging them you will never write again.”

>> Read more: How to make time to write – 4 approaches to finding time in busy schedules

The novelist Henry Miller worked every day for two or three hours in the morning and he thought it was important to cultivate a daily creative rhythm: “I know that to sustain these true moments of insight one has to be highly disciplined, lead a disciplined life.” W.H. Auden thought routine to be a sign of ambition, and he followed an exact timetable throughout his life believing it to be essential to his creativity. His advice to subjugate the muse was the following: “decide what you want or ought to do during the day, then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble.”

“decide what you want or ought to do during the day, then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble.” W.H. Auden

When Haruki Murakami is working on a novel, he follows a solid routine where he works in the morning after waking up, then does something unrelated to his writing in the afternoon―such as exercising, reading and listening to music. In 2004 he told The Paris Review: “The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.”

Feeling like you are at the mercy of outside forces that ‘feed’ you ideas won’t give you the confidence you need in order to write, and it will likely cause unneeded anxiety. Ever heard the phrase ‘appetite comes with eating’? Take control of your own writing by getting down to work regardless of how you are feeling; when the ideas come, you will be ready to receive them (author Elizabeth Gilbert’s Ted Talk might help convince you).

4. Their magic number is three

Granted, there are many writers who swear by writing all day or all night (Karl Marx and Friedrich Schiller, respectively), and some who even work 24 hours straight (James T. Farrell). However, these are mostly exceptions. The key for most writers is to find a time in their day when they can work uninterrupted, usually for 2 to 4 hours per session (sometimes having more than one session a day). For many, the optimal length seems to be around the 3-hour mark.

“The key for most writers is to find a time in their day when they can work uninterrupted, usually for 2 to 4 hours per session.”

Willa Cather worked from two and a half to three hours a day, believing that she would not gain anything by writing for longer hours. John Updike liked to dedicate at least three hours a day to whichever project he was working on at the time. Joseph Heller wrote for two to three hours every night for eight years in order to complete Catch-22. Anthony Trollope, who would write in the morning before going to work, believed that “three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write”, as long as he worked continuously during that time.

The human brain can only sustain so many hours of deep concentration, after which working may even prove counter-productive (Carl Jung strongly believed this) ―great news for those who don’t have a lot of time to write. Morning, afternoon, or night, reserving just a few hours during the day for your writing and ensuring that you are in an environment conducive to deep concentration is key to making progress.

Experiment to find your daily rituals

If there is one thing that Daily Rituals shows, it’s the importance of experimenting to find what works for you. Most of the writers in the book tried out different things and changed their methods multiple times over the course of their life.

Identify what helps you concentrate and write, what hobbies you can take up to complement your writing efforts and help your mind be creative.

Take charge of your creative outputs and show up to do the work even if you don’t feel ‘inspired’. Often the ideas come once you start writing. Finally, identify a time in your day when you can work uninterrupted for a few hours and really focus.

>> Read more: Writing systems: finding yours, why it matters

Daily Rituals has certainly made me think about how I approach my own writing and what I have yet to try. I would encourage you to have a read yourself, this fascinating book has a habit of producing epiphanies. Once you have found what works for you, sticking to it is crucial. Test your routine constantly, stretch it to its limits. In the words of the American novelist and short story writer Bernard Malamud: “Eventually everyone learns his or her own best way. The real mystery to crack is you.”

“Eventually everyone learns his or her own best way. The real mystery to crack is you.” Bernard Malamud

All quotes are from ‘Daily Rituals’ by Mason Currey, Picador, 2013.